A System of Contexts for the Analysis of Electroacoustic Music

Guillermo Pozzati

Department of Music, Universidad Nacional de las Artes, Argentina

guillermopozz [at] gmail.com

Abstract

A system of contexts for the analysis of electroacoustic music is introduced. Four different types of context are considered and taken as the basic components of a theoretical system for musical analysis. On the one hand, there is the context defined by the work itself, made up of all the sounds, structures, events and sound objects that are part of the piece and whose organization allows the work to be identified as such, as a unit. On the other hand, there is the context formed by all the baggage of knowledge, experiences, expectations, beliefs and assessment criteria that the listener has built or acquired prior to listening to the piece of music. Two types of sub-contexts within the piece are also taken into consideration, the one defined by isolated sounds and that defined by musical segments encompassing several sounds. To explore the interactions between these contexts eight types of relationships between them are defined and examples of how they operate in real musical pieces are given. A multitude of usual terms and concepts in musical analysis such as reduced listening, fractality, sound, musical piece, musical style, etc. are reviewed in light of these interactions.

Keywords

Electroacoustic music, system of contexts, focal pitches, analysis, reduced listening.

전자음악 분석을 위한 문맥의 시스템

기예르모 포자티

국립예술대학교 음악대학, 아르헨티나

guillermopozz [at] gmail.com

초록

전자음악의 분석을 위한 문맥의 시스템을 소개한다. 네 가지 유형의 문맥을 고려하여 음악분석을 위한 이론적 시스템의 기본 구성요소로 활용한다. 우선, 있는 그대로의 그 작품 자체로 정의되는 맥락인데, 작품을 구성하는 모든 사운드, 구조, 이벤트, 소리개체들은 그 작품의 부분으로 이들이 유기적으로 혼합되며 한 단위로서 그 작품으로서의 정체성을 갖게 한다. 다음은, 청자가 음악을 듣기 전에 가지고 있었거나 만들어진 지식, 경험, 기대, 신념, 평가 기준 등 모든 마음의 덩어리로 형성된 문맥이 있다. 두 가지 유형의 작품 내 하위 문맥도 고려하였는데, 그 중 한가지는 동떨어진 독립된 소리에 관한 것이고, 다른 하나는 몇 가지 사운드를 포괄하는 음악 세션segments에 대한 것이다. 이러한 문맥간 상호작용을 탐구하기 위해 여덟 가지의 관계유형을 정하고 어떻게 실제 음악작품에서 작용하는지 예시를 들어보았다. 감축된reduced 청취, 프랙탈성fractality, 사운드, 음악작품, 음악적 스타일 등 음악분석에서 사용하는 많은 일반 용어와 개념을 이러한 상호작용의 관점으로 검토하였다.

주제어

전자음악, 문맥의 시스템, 중심 음고, 분석, 감축된 청취.

The core of this article is divided into three parts. The first part presents different contexts involved in listening to electroacoustic music. Their general characteristics are described and, in some cases, specific analytical tools are proposed for its study. The second part shows how these contexts interact with each other. Eight types of binary relationship between contexts are presented and phenomena arising from these relationships are examined. Finally, the third part provides additional examples that illustrate how these contexts work cooperatively functioning as a true system.

Part I: The Contexts

There are four types of context that will be considered in this paper and that are involved in listening to electroacoustic music. They are defined by:

• The inner content of individual sound objects.

• Musical segments that encompass various sound objects. These contexts will be called local contexts.

• The musical piece.

• The knowledge, experiences, expectations, beliefs and assessment criteria that the listener has built or acquired prior to listening to the piece of music. This context will be called the external context.

They will be denoted by the letters w, x, y and z, respectively. Each of them is discussed separately below.

The Inner Content of Individual Sound Objects (w)

Each sound object defines a context. It defines a border that separates what is part of it from what is not. This means that no matter how complex the interior context of a sound object is, it will be perceived as the internal richness of a single sound. We now present concepts that prove useful for the analysis of the interior of a sound object.

First and second order focal pitches. There are sound objects of a certain duration and complexity in which it is possible to clearly perceive one or more pitches that become the focus of attention during listening. These pitches can form true internal melodies that characterize the evolution of the sound object. They will be called first-order focal pitches. It is very useful to analyze a sound object by locating first-order focal pitches on its spectrogram. This allows a 'spectral dissection' operation that consists of separating the focal pitches on the one hand and the rest of the sound object without those focal pitches on the other. In this remainder, other focal pitches may eventually be perceived that had not been consciously initially detected. These new focal pitches, if any, will be called second order focal pitches. The concept of focal pitch can be generalized to that of focal element to encompass any characteristic of the sound object that is relatively stable and with high salience.

Internal rhythm. Perceived changes in the spectral quality of a sound object can give it an internal rhythm. A particular case is when a first-order focal pitch presents perceptually clear amplitude oscillations whose peaks (local maxima) do not exceed on average five or six per second.

Local Contexts (x)

A local context is a musical segment that encompasses various sound objects. Local contexts are organized hierarchically, the large ones encompassing the smaller ones.

The Musical Piece (y)

It is the context defined by the piece itself. It is made up of all the sounds, structures, events and sound objects that are part of the piece and whose organization allows the work to be identified as such, as a unit.

The External Context (z)

It is the context formed by all the baggage of knowledge, experiences, expectations, beliefs and aesthetic-musical assessments that the listener has built or acquired prior to listening to the piece of music. Included here is the listener's knowledge of sounds from the external world, including their causes and meanings. His or her knowledge about works, musical styles, musical composition and technological tools related to the creation of electroacoustic works also belong to this context. The listener's perceptual capacity is also part of the external context.

Previous Work on Contexts

Innumerable references to factors external to the work can be found in the literature, for example:

In my discussion of music, I would like to use the term 'mimesis' to denote the imitation not only of nature but al-so of aspects of human culture not usually associated di-rectly with musical material. (Emmerson 1986)

The existence and usefulness for the analysis of contexts of type w and x also has antecedents in the literature. See Smalley's distinction between texture-carried and gesture-carried. Even the term context is used in the following quote:

... we can refer to the context as gesture-carried or texture-carried. (Smalley 1997)

In relation to the transition from one type of context to the other, Smalley uses the expression.

We seem to cross a blurred border... (Smalley 1997)

This leads us to the next section.

Borders between Contexts

There are sound events that inhabit a border area between contexts of type w and type x. Between one type of context and another there is a diffuse zone, of transition. It is possible for example that certain events are halfway between roughness and fast iteration. In other words, between a context w (a sound object with rough quality) and a context x (that presents in rapid repetition a version without roughness of that same sound object). This transition zone is related to the way perception processes acoustic changes at different time scales. Its musical importance is echoed in the following statement by K. Stockhausen.

Thus the transition from one time-area to another causes a change in our perception of phases. This observation could form the basis of a new morphology of musical time. (Stockhausen 1959)

A musical example that exploits this transition zone is presented in the third part of this paper1.

Contexts and Time Scales

C. Roads (2001) lists nine time scales. There is a correlation between the contexts of type y and z with the macro- and supra-time scales, respectively. Likewise, it is tempting to relate contexts of type w and x with the sound object time scale and the meso time scale. However, a context of type w is defined more by qualitative factors rather than quantitative/ temporal issues. The defining quality of type w is that it is texture-carried, in Smalley's terms. A three-minute drone is a w-type context, and a half-second melodic gesture, made up of three pitches in rapid succession, will define a type x context as long as the listener hears that there is more than one sound in that unit.

Contexts and Musical Entities

Many relationships involving sound objects and local contexts (Rww, Rwx, and Rxx) can be based on the same common nucleus. That nucleus can be a sound, a spectral quality, a succession of pitches, etc. The different variants around this nucleus will be perceived as different facets of the same entity (and not as different entities). The contexts involved in these relationships are the 'stage' where an entity is presented from multiple perspectives. Each recontextualization of the nucleus gives rise to a new experience that adds to the previous ones to favor a deeper understanding. Each new perspective reveals a particular manifestation of something more general. A geometric analogy seems pertinent. A cube viewed from the front looks like a square. If you look at it from another perspective, you can see other faces. The experience offered by each new angle of observation is integrated with the previous ones and deepens the understanding of the object of perception. The different experiences are not associated with different entities but with different facets of the same entity. The third part of this paper presents a detailed example of an interval (C-G) that through successive recontextualizations leads to diverse musical meanings. It will also be seen that each pitch of this interval tells a different story, C changing its spectral quality and G crossing the boundary that leads from roughness to iteration, that is, it crosses the dividing line between contexts of type w and contexts of type x.

Part II: The Eight Types of Intercontextual Binary Relationship

In this section, eight types of binary relationship between contexts will be derived. For this, it is necessary to know the type and quantity of contexts that a piece of music can have. Usually a piece presents several sound objects. Each of them defines a context of type w. Sound objects are integrated into larger, hierarchically organized units. These units define contexts of type x. It is evident then that there are many contexts of type w and type x in the same piece of music. Rather, there is a single context of type y and a single context of type z for each particular listener (the piece itself and the background of that listener, respectively). Each type of context is related to others of the same type, in case there is more than one context of that type, and also to each of the other three types of context. This creates eight fundamental types of relationship between contexts: Rww, Rwx, Rwy, Rwz, Rxx, Rxy, Rxz, Ryz.

Relation Rww

Any relationship between two sound objects is a relationship of type Rww. The relationship between two sound objects can be complex and reveal the potential information that the second object generates by 'reinterpreting' focal elements of the first object. By way of illustration, it is useful to compare the first sound object of the work Base Metals, by Dennis Smalley, with another sound object of the same piece that begins at 3' 05''.

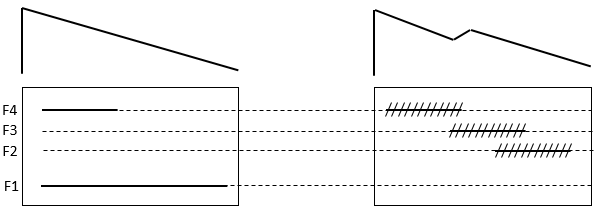

Figure 1.

Diagram of some relationships between two sound objects taken from Base Metals, by D. Smalley.

Sound 1. (Fig. 1 Left) - Initial sound object in Base Metals by D. Smalley.

Sound 2. (Fig. 1 Right) - Sound object at about 3' 05'' in Base Metals by D. Smalley.

The first object has two first-order focal pitches, the frequencies of which are indicated as F1 and F4 in Figure 1. The second object has F4, but not F1. The retained focal pitch that was perceived clean in the beginning is now affected by roughness by the presence of spectral energy at frequencies adjacent to F4 and followed by other first-order focal pitches of frequencies F3 and F2 that altogether originate a true internal melody. The top part of the figure also shows the amplitude envelopes of both sound objects. Later in this paper it will be shown how these envelopes, among other factors, influence in different ways the relation of these sounds with the external context.

Relation Rwx

Any relationship between a sound object and a local context is a relationship of type Rwx. The nature of the Rwx relationship determines whether a sound object is integrated with others in a single gesture or if it contrasts with what surrounds it thus acquiring a particular relief. The study of Rwx also allows us to better understand the different types of interaction that can occur between the interior of a sound object and what is outside it. Two types of interaction between a sound object and a local context are examined below, which will be called combination rhythm and projection, respectively.

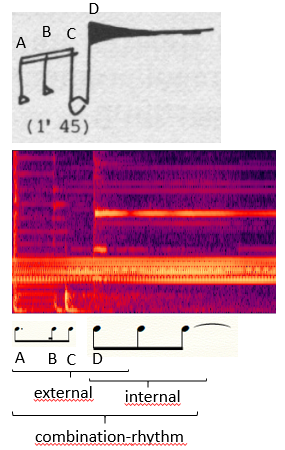

Combination rhythm. It is a particular type of interaction between a sound object and its own local context. It combines the traditional notion of rhythm with that of the 'internal rhythm' of sound. The traditional notion of rhythm assumes a relationship between two or more different sounds. An isolated sound is not in itself a rhythm. To be part of a rhythm that sound needs to 'connect' with others. Rhythm is a phenomenon 'external' to individual sounds. In electroacoustic music, on the other hand, it is also common to find sounds that have an 'internal rhythm'. The combination rhythm is that formed by the combination of the internal rhythm of a sound object with the external rhythm that it forms with the sounds that surround it. B. Parmegiani made a graphic transcription of his composition De natura sonorum. At time 1 '44'' of the first Étude (Incidences / résonances) this transcription symbolically reflects four consecutive sound objects. At the top of Figure 2 are the symbols used by Parmegiani for these sounds. The letters A, B, C and D are not part of the original transcription but have been added here to identify the four sound objects in this fragment. The last one (D) has an internal rhythm that interacts with the external rhythm defined by the preceding sounds. The internal rhythm of D is reflected in the spectrogram.

Figure 2.

Combination rhythm formed by the interaction between external rhythm and internal rhythm.

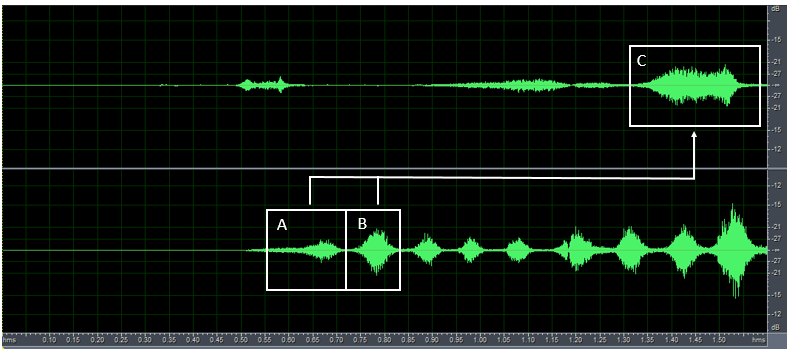

Projection. This type of interaction takes place between a sound object and a local context, which may or may not be the same one in which said sound object is presented. The fundamental idea is that there are relationships that originate between different elements of a local context that can be 'projected' inside a sound object. In other words, the internal life of a sound object reflects processes that take place outside of it. Something that happens in a context of type x is projected onto one of type w. Consider for example two consecutive vowel sounds, instances of the phonemes / u / and / a /. It is possible to project the relationship between these two sounds into a single sound object, whose internal life is based on the continuous transformation that leads from one to the other. The beginning of the Étude Élastique, by B. Parmegiani, provides an example (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Projection of the sequence A-B inside C

Sound 7. (Fig. 3) Beginning of the 'Étude Elastique' by Parmegiani.

The sequence of sounds A and B in the right channel is projected shortly after to the left channel inside sound C.

Sound 8. (Fig. 3) Sequence of sounds A and B in right channel.

Sound 9. (Fig. 3) Projection of the previous sequence on sound C, in the left channel.

Relation Rwy

This relationship takes the whole of the piece as the environment of a particular sound object and analyzes how the context of type w defined by this particular sound object is related to everything that happens in the piece. It is here where the extraordinary potential characteristics of this sound object emerge with respect to all the others present in the analyzed composition. The first movement of G. Ligeti's chamber concerto for 13 instrumentalists presents an exceptional event consisting of a long ‘E flat’, tenuto, pp, senza vibrato that sounds in five octaves. In the context of the piece, this event marks a before and after. On the contrary, the pronunciation of the letter 'C' in the composition entitled ABC by P. Lansky, is a salient event only at the level of its own local context, since it is the only vowel sound that is heard in about half a minute. However, considering the complete piece it is clearly seen that it is one more vowel sound among many other vowel sounds that appear when pronouncing other letters of the alphabet. We will return to this piece in Part III.

Relation Rxx

Local contexts are organized hierarchically, the large ones encompassing the smaller ones. Rxx is the relationship between two local contexts, of the same or different structural level. When the related local contexts belong to different structural level, Rxx can reveal interesting phenomena, for example that a small local context summarizes what happens in another of a higher level. Just as a local context can be projected inside a sound object, a local context can be projected onto a lower level one. This idea of projecting the large into the small is at the heart of fractality.

Relation Rxy

This relationship allows to have the complete panorama of the structure. The piece shows the relative temporal position of each local context, which defines its formal function in the whole (exposition, development, 'reprise', etc.).

Relations Rwz , Rxz y Ryz

These relationships originate the phenomena of quotes, referentiality and evocation. Also the different listening modes enunciated by different authors are determined by the nature of these relationships. For example, attenuating or eliminating (if this were possible) the relation Rwz, that is, the relation between a sound object and the external context, leads to the concept of reduced listening by P. Schaeffer. On the contrary, in D. Smalley's so-called technological listening, we have that the relations Rwz, Rxz and Ryz displace the others:

Technological listening occurs when a listener ‘perceives’ the technology or technique behind the music rather than the music itself, perhaps to such an extent that true musical meaning is blocked. (Smalley, 1997)

The 'invasive' role of the external context is clear. The 'blocking' of musical significance mentioned by Smalley in his quote coincides with the idea that the three relations discussed here can displace the internal relations Rww, Rwx, Rwy, Rxx and Rxy. In other words, the relationships that involve the external context are imposed on the others in a particular and excessive way. The system of contexts is an analysis tool and accounts for this scenario without condemning it, admitting it as one more way of 'listening' among other possible ones. For Smalley, however, this situation does not lead to "true musical meaning".

The Rwz relationship of each of the sound objects represented in Figure 1 reveals that the first of them has a high referential power to a bell-like sound. The second, on the other hand, does not refer to the external context with the same force due to its amplitude envelope and the roughness of the focal pitches, among other factors. At most it can be interpreted as a 'sonic metaphor' for a bell-like sound.

Any observation regarding the style of a piece of music involves examining a Ryz-type relationship.

The z context of the composer. A case of particular interest is that of the composer, who during the composition of the work has probably heard the sounds of his piece dozens of times, both separately and in different combinations, always carefully and critically examining its constructive and functional potential. The final version of a sound object may be the latest in a series of refinements on previous versions. The composer will be able to identify the sounds with which he worked even when they are part of complex textures. Obviously, the rest of the listeners, who have not had the experience of listening repeatedly and separately to the sound objects, will perceive the music in a different way from that of the composer. The context z of the listeners is very different from that of the composer. The composer often assumes that what he or she hears is similar to what the audience of his or her piece hears in the first place. The composer's context z has unique peculiarities, so it is not possible to expect a high intersubjective correlation between this context with the z contexts of other listeners.

The eight types of binary relationship presented in this section operate simultaneously in the musical phenomenon. Changing one of these relationships affects the other seven2.

Part III: Additional Examples

This section presents concrete examples of how the system of contexts operates in electroacoustic works.

ABC by Paul Lansky.

The listener's expectations system can be activated through the use of 'cultural objects' external to the work, objects that the listener knows and whose sequential structure allows predicting its normal continuation. For example the alphabet (a, b, c, d, etc ...) or the natural numbers ordered from least to greatest (1, 2, 3, 4, etc ...). The piece ABC by P. Lansky provides a clear example. After having heard the sounds corresponding to 'a', 'b', 'c', ... the listener expects ... 'd', and then ... 'e'. The internal context of the piece favors this tendency, making the time distance between one letter pronunciation and the next always the same. In the absence of temporal regularity, the predictive power generated by the alphabet alone is weakened. It is the mutual cooperation between the external context and the internal context that arouses the emergence of expectation regarding the appearance of the next letter pronunciation. This analysis is an example of a Ryz-type relationship. As an example of a relationship of the type Rwx, consider for example the sound object that corresponds to the letter 'C' and its local context. In the sound object a noise component and a downward pitch inflection are perceived successively. There are no other vowel sounds in the vicinity (the previous one occurred 16 seconds before and the next will come after 16 seconds). In this way, the local context contributes to the local salience of the sound of the 'C', allowing the memory to record it firmly. Significantly the downward pitch inflection of the sound object lands on the pedal note that is sounding from the very beginning of the piece. This agreement between the last part of a sound object with its local context of getting the same note gives rise to a subtle effect of resolution.

Break Up by Jorge Rapp.

The first CD of electroacoustic music edited in Argentina includes the work Break Up by Jorge Rapp. The piece reaches a climax and, after a brief silence, allows to hear an applause, which creates the impression that the work is applauding itself, thus usurping the role of the audience. This is a particular case of a Rxz relationship.

Sound 10. Excerpt of Break Up by Jorge Rapp.

Smalltalk by Paul Lansky.

The work Smalltalk, by Paul Lansky, conveys the most subtle nuances and inflections of the human voice in the context of a conversation. However, the only thing that the composer leaves hidden at the beginning of the piece is, precisely, the vocal timbre; instead uses a plucked string sound. At a given moment, almost in a ghostly way, the voice is glimpsed for very short moments and deep in the background, as if it were revealing its presence from a hiding place, which leads to a retrospective resignification that allows us to understand that the voices were there from the very beginning of the piece, but the awareness of this does not occur until later. This phenomenon shows that the relationship of a musical piece with an element of the external context may be different from the explicit quote or reference.

Chopin by Guillermo Pozzati

The piece uses piano sounds to quote passages from Chopin's waltz Op. 64 No. 2 and also uses human voices to pronounce the name of the aforementioned composer in French. The listener who knows Chopin and his work then connects on the cognitive plane sounds as different as that of a piano and that of the human voice. The unit is then supplied by the relations with the external context (relations of the type Rwz and Rxz) and not by internal relations.

El Sendero de Cristal by Guillermo Pozzati

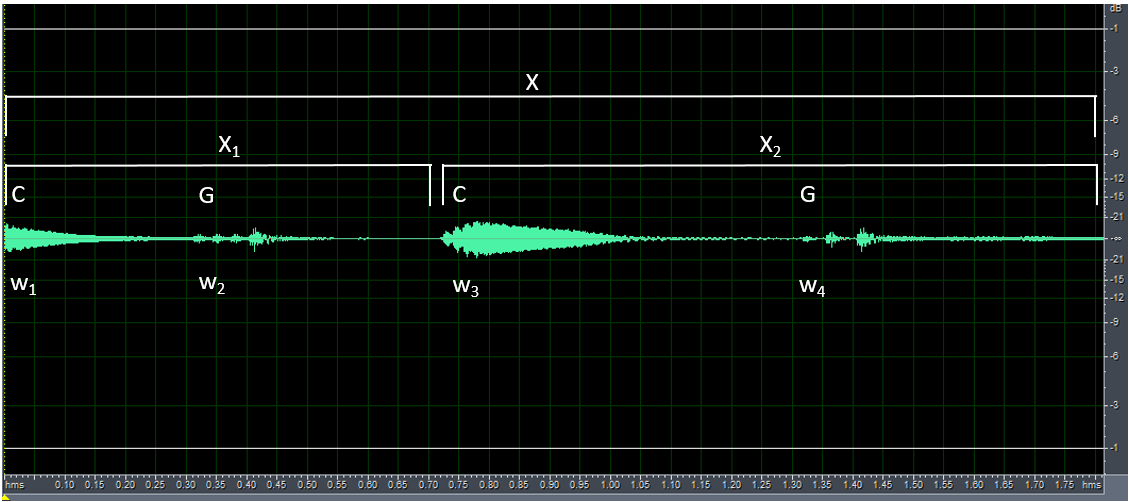

The following analytical comments are based on the stereo version of this piece . Figure 4 shows the content of the left channel at the very beginning of the work. It is a local context, x, which encompasses two lower-level local contexts, x1 and x2, both have a common nucleus, the succession of pitches C-G. x2 provides a new perspective in time with respect to x1, it shows that the separation in time between C and G can be greater than at x1. In other words, after C, G may take longer to appear. Resignifications such as the one described occur in local contexts whose duration and complexity is compatible with the capacity of the listener's short-term memory. When x2 starts, features of x1 are in short-term memory and in this way perceptual data can be integrated and give rise to new meanings.

Figure 4.

Two local contexts with a common nucleus, C-G. The separation time between the two pitches is longer at x2 than at x1.

Sound 11. (Fig. 4) Local context x showing two temporal perspectives of the interval C-G.

The sequence of sounds A and B in the right channel is projected shortly after to the left channel inside sound C.

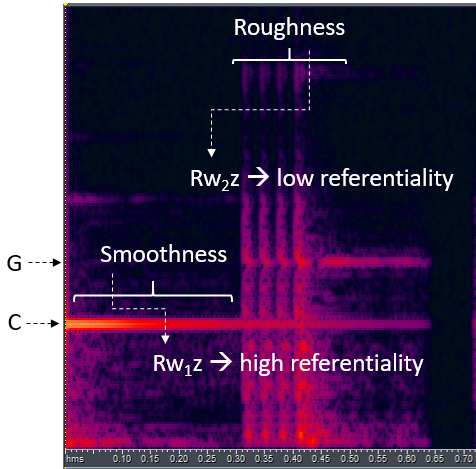

The spectrogram of x1 is shown in Figure 5. It reveals oscillations in the spectral energy of G that are perceived as roughness. While Rw1z shows referentiality to piano sound, Rw2z is weaker in that sense, roughness weakens referentiality to piano.

Figure 5.

Spectrogram of x1.

Sound 12. (Fig. 5) Local context x1.

This passage has been analyzed as the sequence of two sound objects, the first based on a C with a piano sound and the second based on a G with a rough quality. Actually C does not disappear when G enters, which can be seen in the spectrogram, but the preeminence of the latter justifies the analysis.

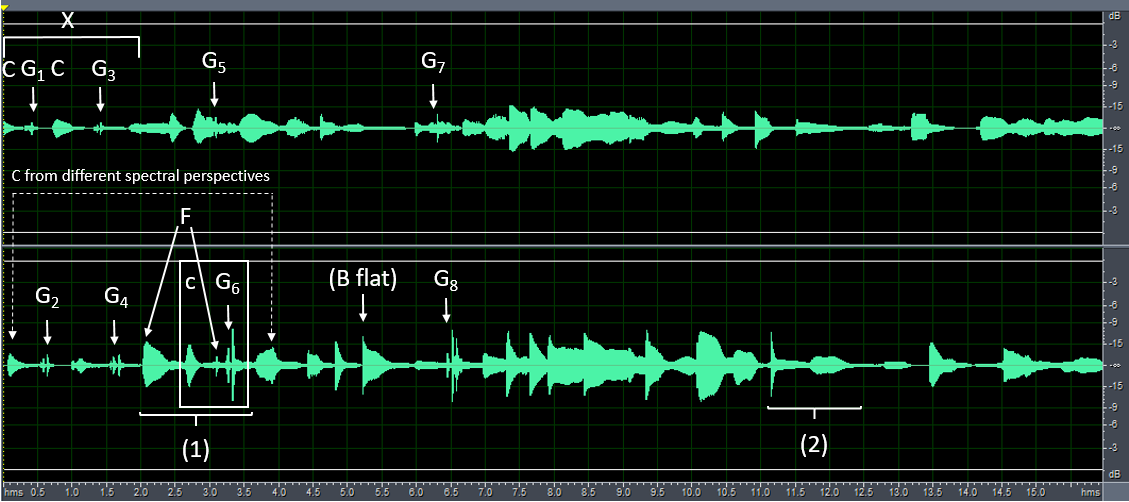

Figure 6 shows a higher-level local context of approximately 16 seconds duration that encompasses the previously analyzed context x. The succession of pitches C-G that x presented from two different perspectives, is presented in this longer segment from multiple perspectives. One of them, boxed in the figure, occurs a little more than two seconds later in the right channel. The information supplied is multiple, the 'C' is rough (the referentiality to the piano sound is weakened), the G is crossing the border that goes from roughness to the fast iteration (the referentiality to the piano sound is strengthened) and, finally, a pitch F that had been clearly heard a moment before appears sandwiched between the two base pitches.

Each note tells its own story. G moves from pianissimo to fortissimo, from roughness to rapid iteration and delays its appearances until it disappears. In Figure 6 eight occurrences of this pitch are indicated. In the right channel, at time 6.4s, G crosses the boundary that divides the roughness of the iteration.

Figure 6.

First section of the piece

Sound 13. (Fig. 6) First section complete of "El Sendero de Cristal"

The sequence of sounds A and B in the right channel is projected shortly after to the left channel inside sound C.

Sound 14. (Fig. 6) G1: roughness.

Sound 15. (Fig. 6) G8: iteration.

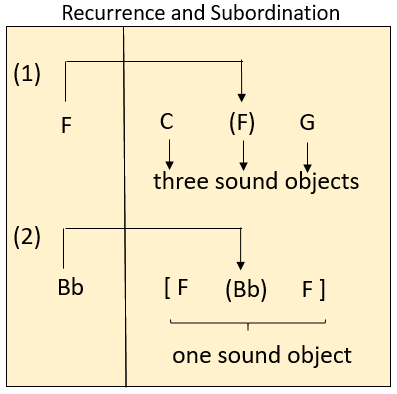

This is the last appearance of G in this segment that constitutes the first section of the piece. Here G acquires a new harmonic meaning by the influence of the preceding B flat. On the right channel, beginning at time 11.1s, two sound objects are heard. In the figure they are indicated with the horizontal curly bracket (2). The first presents a B flat and the second an F, but the internal life of this last sound allows the previous B flat to be heard fleetingly. When comparing this process with the one indicated with the curly bracket (1) - which includes the previously analyzed example of F inserted between C and G - it is seen that in both cases there is an isolated pitch that reappears immediately subordinate to others (or another) different. The difference lies in the way they reappear, while F reappears as an independent sound object, B flat reappears instead as part of the internal life of a single sound object. Figure 7 schematically shows the aforementioned difference.

Figure 7.

Two cases of recurrence with subordination of the same pitch.

C, for its part, is presented from different spectral perspectives. Compare in the right channel the two occurrences of C indicated in Figure 6 with a dotted arrow. The second C has a lot of energy above 4000Hz.

Sound 18. (Fig. 6) First 'C' indicated by the dotted arrow (C from different spectral perspectives).

It is also possible to perceive in the spectral evolution of the second C an incipient projection of the local context x1.

Sound 20. (Fig. 4 & 5) Local context x1

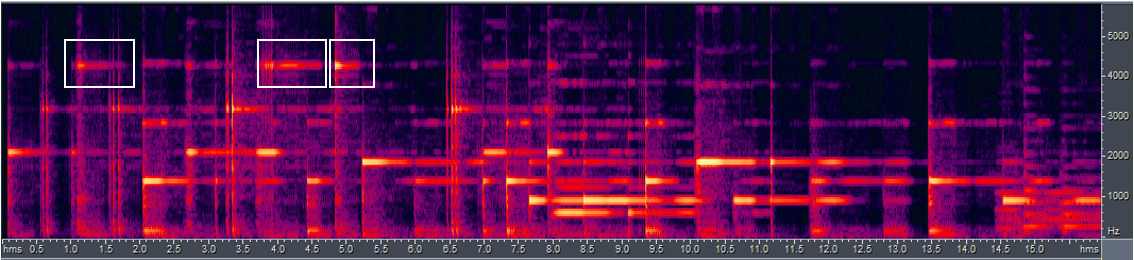

This relatively high level of spectral energy above 4000Hz is a recurring phenomenon in the first seconds of the right channel whose spectrogram is shown in Figure 8.

Clearly audible energy peaks are shown with rectangles. The second rectangle corresponds to the second C just mentioned.

Figure 8.

Spectral energy peaks above 4000Hz in the right channel.

Finally, a relationship between this first section and the end of the piece is analyzed. The work ends with a sound object lasting more than 20 seconds. The main notes of both sections together form a diatonic network. In the beginning the notes are mostly parts of different sound objects. In the end, the notes form the inner life of the sound. They characterize layers of a texture that constitutes the very fabric of the final sound object. This is an example of Rwx, where the time scale of the sound object is the same as that of the local context.

Sound 22. The end of "El Sendero de Cristal". The internal life of the sound has a diatonic quality.

Conclusions

This paper has presented a system of contexts relevant for musical perception and examples that suggest how this system can be used in the analysis of electroacoustic music. Perhaps the greatest utility of the presented approach is that it offers a unified view of concepts and terms as disparate as section, reduced listening, fractality, sound, musical piece, style, etc. The ideas presented in this work can also be of benefit to the composer since they do not imply any imposition of technical or aesthetic restrictions. The system of contexts will always be operating, regardless of whether the composer is aware of it. Knowing the interactions of this system invites us to explore its concrete possibilities musically, always with the freedom that art supposes.

References

Emmerson, Samuel. (1986). The Relation of Language to Mate-rials. In Emmerson, S. The Language of Electroacoustic Music. London, Macmillan Press Ltd: 17.

Roads, C. (2001). Microsound. The MIT Press.

Smalley, Dennis (1997). Spectromorphology: explaining sound-shapes. In Organised Sound (2/2). Cambridge University Press: 107-126.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz (1959). ... how time passes... In Die Reihe (Vol. 3). English translation. Theodore Presser Co./Universal Edition.

1. Frontiers with the z-type context should also be considered, since the very act of perceiving involves the listener's mind. For our purposes it will suffice to say that the external context op-erates at its minimum if the perception is not strongly influ-enced by previous experiences and does not trigger those high-er-level cognitive processes related to source recognition, evo-cations or other particular phenomena related to long-term memory.

2. An interesting example is offered by Schaeffer's observation that we can forget meaning and isolate the in-itself-ness of the sound phenomenon by means of repetition. His statement is almost equivalent to saying that in order to obtain a null rela-tion between a sound object and the external context it is effi-cient to create an artificial local context based on the repetition of that sound object!

3. Originally composed in 3rd. order Ambisonics and rendered for a 24.8-channel immersive system in its premiere on August 2021 at the 2nd. CCRMA Transitions concert.

논문투고일: 2021년 09월28일

논문심사일: 2021년 11월30일

게재확정일: 2021년 12월02일